The lost honour of …

Written by Rob on september 3, 2020

A number of publications bears a title that starts with ‘The lost honour of …’.

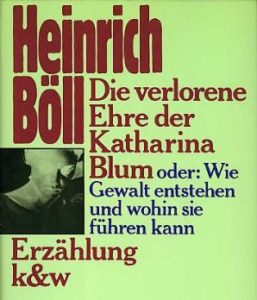

For example, in 1974 the German writer and later Nobel prize winner Heinrich Böll (1917-1985) published his classic novel ‘Die Verlorene Ehre der Katharina Blum. Oder: Wie Gewalt entstehen und wohin sie führen kann.’

In 2014 the film ‘The Lost Honour of Christopher Jeffries’ was broadcasted on television (dir. R. Michell), based upon actual events.

If we are to believe the publications on honour and honour related violence, titles like these are impossible.

According to those publications, honour related problems are always related to so-called (non-western) cultures of honour with their codes of honour.

So one wonders why a German author and a British art director would choose titles like these.

‘Cultures of honour’ and ‘codes of honour’

The notion of ‘Cultures of honour’ concerns mainly non-western men and women; if they trespass the honour codes of their ‘culture’ (or their families), they will get in conflict with family members who will then consider their honour damaged. This will lead, in this reasoning, to conflicts and honour related violence.

In many publications there is little sympathy for (non-western) individuals who claim that they ‘lost’ their honour. The assumption is that they use ‘honour’ as a pretext to oppress others, in particular women.

Germany and the UK are no ‘cultures of honour’

But Germany and the UK are ‘western’ countries and for this reason their societies are never listed among the ‘cultures of honour’ with their ‘honour codes’.

In the UK and Germany a ‘lost honour’ is unlikely to be a serious problem

In view of the fact that a ‘lost honour’ of an average German or Briton, in this reasoning, is impossible, one is inclined to think that it cannot be very problematic for them to ‘lose’ their honour.

Let us investigate what these two stories have in common, and what Blum and Jeffries actually ‘lost’, if anything.

The book and the film

Böll’s novel became a world wide classic and was translated into numerous languages. It formed the base for a German film in 1975 (V. Schlöndorff, M. von Trotta).

The British film, consisting of two parts, from 2014, which described the story of Christopher Jeffries, won two important British prizes: one for the film and one for actor Jason Watkins.

Katharina Blum

Katharina Blum (27), known as a reliable, friendly young woman, works as a housekeeper for a wealthy family. During a dancing night she meets an attractive and charming man, Ludwig Götten. Before they know, the two are bound to each other and land in Katharina’s bed.

Katharina Blum (27), known as a reliable, friendly young woman, works as a housekeeper for a wealthy family. During a dancing night she meets an attractive and charming man, Ludwig Götten. Before they know, the two are bound to each other and land in Katharina’s bed.

In the morning Katharina wakes up when a police arrest team storms into her bedroom. Ludwig, who had already left, turned out to be a criminal, wanted by the police. Katharine is taken to the police station for interrogation.

The press jumps onto the case

The press hear about the case. Journalists of the gossip magazine Die Zeitung question friends and acquaintances of Katharina’s, but their words are published turned and twisted.

Thus, a picture of Katharina is created as a lustful, promiscuous woman, who is a calculating and opportunistic mistress to criminals and terrorists.

While Katharina is still in detention, a journalist of Die Zeitung, Werner Tötges, even visits Katharina’s mother, who lies ill in hospital, and confronts her with this terrible image of her daughter. One day later, she dies.

Katharina grows desperate

Eventually Katharina is released again. But she is far from relieved. Her mother died in misery. She daily receives anonymous obscene telephone calls and letters. Her friends are under pressure as well because of her. Katharine has become an outsider in her community. Her life is devastated.

She decides to do something about it. She decides to meet with journalist Tötges, and shoots him.

Christopher Jeffries

Christopher Jefferies (65) is a retired teacher of English living in Bristol. He owns a large house in which appartements have been built, which he rents out. From October 2010, one appartment is rented to landscape architect Joanna Yeates (1985) and her boyfriend Greg.

On December 17, 2010 Greg reports Joanna missing. A week later she is found murdered elsewhere in Bristol.

Soon Yeates’ landlord, Mr Jefferies, is taken to the police station as a suspect and held in custody. After a few days he is released on bail, but remains under suspicion.

The press accuses Mr. Jefferies

Then the gossip press jumps on Mr. Jefferies. What is a godsend for the gossip press journalists is that Christopher Jefferies is an elderly eccentric bachelor, who has long, greying hair, who formulates and articulates in a peculiar manner and recites poetry and literature.

Journalists publish, fed by information from police, all kinds of exaggerated and fabricated stories about the murder and Mr. Jefferies’ alleged role in it. Among other things, they assert that Jefferies secretly observed Joanna.

Statements from Jefferies’ neighbours, former students, friends and acquaintances appear twisted in the newspapers. Jefferies is not able to leave his home, afraid of being persecuted by journalists and scolded at by neighbours and acquaintances. Notwithstanding, Jefferies could count on a group of friends that kept supporting him.

Another suspect is arrested

In January, 2011 Yeates’ next door neighbour, the Dutch expat Vincent Tabak (1978) is arrested. After some time he confesses to manslaughter and is convicted to a life sentence in October 2011.

Yet only in March 2011 Jefferies is discharged and his bail lifted. Jefferies begins a number of cases for libel and slander against the police and the gossip press, which he all wins.

Agreements between the two cases

Both the book and the film deal with an individual who is suspected of some major misbehaviour. Despite indications for their innocence, not only the press, but also the authorities keep hinting at their involvement. This feeds gossip and headlines in the media. They are branded and stigmatized.

The press attention enhances and constantly rekindles the suspicions, as a result of which the case cannot come to a rest. The social lives of Jefferies and Blum get completely devastated. Their despair grows.

Differences between the cases

There are also differences between the two cases. Mr. Jefferies was suspected of murder of a young woman: a serious crime.

Katharina Blum was not suspected of having committed a crime, apart from (unwittingly) providing shelter to a wanted criminal. Yet merely because of her alleged intimate relationship with Ludwig Götten, people assumed that Blum knew about his crimes and, in addition, that she did not mind them.

The fact that Blum maintained that she hardly knew him did not make any difference; anyone in her situation would have ample reasons for telling lies about the relationship.

A stigma by association: friends and relatives can easily be dragged into problems because one person’s misery

You could say that Ludwig Götten’s crimes reflected on Katharina because of their alleged intimate relationship. This mechanism is called in social psychology a stigma by association: when a friend of yours or a member of your family commits a gruesome act, you too can be held accountable by your friends, acquaintances and outsiders.

In such situations you have to clarify, in a credible manner, your position regarding your associate and his or her acts and, of course, distance yourself.

In addition, Katharina was depicted as an immoral woman who was ready to go to bed with everyone.

All of this together was enough for her social exclusion.

What was it that Blum en Mr. Jefferies had ‘lost’?

What exactly did Mr. Jefferies and Blum possess or have before all of this happened to them and what got ‘lost’ and at what point?

Prior to the incidents both lived their ‘regular’ lives. They went to their jobs, they had chats with their employers, neighbours, colleagues, friends, tenants, bought their groceries in shops, visited and received friends and relatives, and went to dancing nights.

These ‘regular’ lives came to an sudden end after the accusation. The public accusation, it seems, must have been the turning point.

How can accusations lead to the end of ‘regular’ relationships?

What could be the connection between these accusations on the one hand and the end of normal relations with other people on the other?

The answer is, I think: doubt and mistrust. Because of the public accusations many people started doubting Blum’s and Mr. Jefferies’ sincere intentions and integrity. They began distrusting them.

As a consequence, people started distancing themselves from them, resulting in stigma and social exclusion, which sometimes turned into outright hostility. Such a process itself is not brought about by the (false) messages in the gossip papers, but they certainly enhanced and intensified it.

I think it is fair to say that due to the accusations both of them lost their integrity in the eyes of their community; they lost their moral reputation.

There is another individual who suffers from a ‘lost honour’

In the Jefferies story this is no doubt Vincent Tabak. He is now officially registered as a murderer, there are ample reasons why people doubt his intentions and integrity.

Obviously, a ‘lost honour’ also applies to people who the court actually has found guilty of misbehaviour: both friends and outsiders start distrusting them and keep abay.

Social stigmatization and exclusion are the result of doubt and mistrust

This renders it difficult for former inmates to restore a social life after they served their prison time — a known problem. And their family members and friends too suffer from the burden of a stigma by association.

There are people, among whom his family members, who believe that Tabak has been convicted while innocent. They think he was set up because he was a foreigner (http://vincent-tabak-is-innocent.blogspot.com).

A ‘lost honour’ is a disaster

If we are to believe the stories about Christopher Jefferies and Katharina Blum, a ‘lost honour’ is nothing less than a disaster.

Apparently, a ‘lost honour’ for (non-immigrant) Britons and Germans is not an emotion or a mere excuse for commiting a crime, but an outright nightmarish situation of social exclusion and rejection.

Such situation a is the result of a public accusation, regardless whether it is true.

A ‘lost honour’ makes people feel desperate

If there is one thing we can learn from the two accounts is that a situation of having ‘lost’ one’s honour, is (for Germans and Britons) so hurtful and extreme that individuals feel desperate and are ready to use violence and even commit a murder.

This, I believe, we can call honor related violence.

The German author, Heinrich Böll, already refers to violence in this context in the subtitle of his novel: Or: how violence develops and where it can lead.

In an interview not long after the publication of his book, Mr. Böll said that he had pondered the idea that the heroine, Katharina Blum, commit suicide — which would have been a credible outcome of the story as well. Yet that too would have been a type of honour related violence.

Some final questions …

Having read all of this about a German woman and a British man, do you think it is feasible that the lives of non-western individuals could take a similar disastrous turn?

Having read all of this about a German woman and a British man, do you think it is feasible that the lives of non-western individuals could take a similar disastrous turn?

I mean, is it feasible that a Turk, Arab, Moroccan, Kurd or Pakistani (much like Mr. Jefferies) be rejected by his or her community because he or she has allegedly trespassed important moral borders? (And that the press jumps on to it and makes it worse?)

Is it possible that a Turk, Arab, Moroccan, Kurd or Pakistani man or woman is socially rejected (like Katharina Blum) because an acquaintance or family member of his / hers is being suspected of something terrible?

Is it possible that a Turk, Arab, Moroccan, Kurd or Pakistani man or woman is socially rejected (like Katharina Blum) because an acquaintance or family member of his / hers is being suspected of something terrible?

And because his / her friends, neighbours, colleagues, acquaintances believe that he / she and other family members have no problem with that terrible crime?

Could we in those cases speak of ‘Murat Yılmaz’ lost honour’, or ‘The lost honour of Aisha al-Masri’?

Would you be surprised if a given Murat, Aisha or others in that given context (out of despair) used violence?

Do you, as I do, then wonder how notions like ‘culture of honour’ and ‘honour code’ fit in?

A very interesting comparison of situations leading to accusations by a group. I wonder, can we say that Katharine tried to ‘restore’ her ‘lost honour’ by shooting Tötges? Or was it a desparate act to take revenge of the mass media as an instrument of stigmatisation?

It seems it was an impulsive action. But however understandable, it did not restore her lost honour. It was, I think, a revenge action.